This article was originally published in Forbes and “Deal Points” (Winter 2021 edition), the official newsletter of the Mergers and Acquisitions committee of the American Bar Association.

Recent events have created an unprecedented sense of urgency amongst business owners to consider selling their businesses. The unexpected Georgia election results and resulting Democratic sweep all but guarantee that capital gains rates will increase, consistent with Biden’s tax plan. The impact for business owners will be substantial— If rates double as expected, owners will need to sell for 33% more just to receive the same after-tax proceeds. While no one knows exactly when these changes will go into effect, the conclusion is similar: Owners should consider expediting their sale process to sell within this limited window or risk delaying their exit indefinitely with the hope that a future sweep by a Republican administration will revert rates back.

While higher valuations and growth can help overcome these tax burdens, both will likely encounter headwinds over the medium-term:

- Valuation multiples are at peak levels and have more downside than upside

- US is forecasted to be in a low-growth environment over the medium to long-term

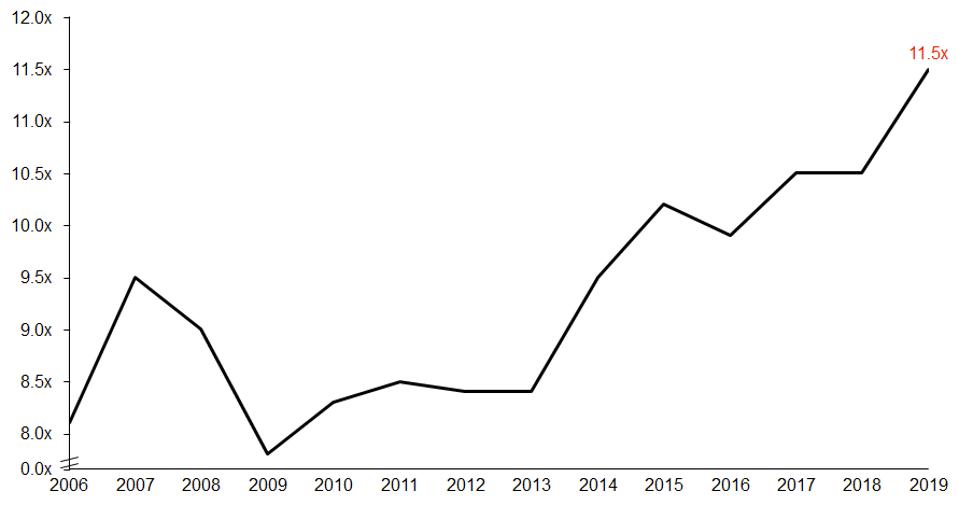

Valuation Multiples Are at Peak Levels

Valuation multiples (often referred to as EBITDA multiples) are generally cyclical, but have continued on a steady rise since the Great Recession to what is likely their highest in recorded history (historical private transaction data is sparse). While the below chart is only through 2019, anecdotal evidence indicates that industries performing well during Covid-19 are commanding multiples that are similar or even higher.

This rise in valuation multiples is primarily attributable to the Fed’s low-interest rates. These low rates help increase the availability of debt financing, which is directly correlated with valuations. Moreover, asset prices have inflated as investors search for higher yields, resulting in an accumulation of excess capital within Private Equity (PE) funds, known as “dry powder.” When these PE funds compete to purchase a business, it nearly always results in prices getting bid up.

A recession is generally not an ideal climate for M&A transactions and valuations to flourish. But this recession, and our world right now, is anything but typical. Covid-19 has forced the Federal Reserve to flood our system with virtually unlimited liquidity at near-zero interest rates. This has allowed aggressive lending to continue at attractive rates, which is the lifeblood of the M&A markets. Moreover, transaction activity came to a standstill during the initial Covid-19 lockdown, so many of these PE funds are playing catch-up in deploying capital.

At the very least, it is unlikely that multiples will rise meaningfully going forward. Given the current peak levels, it’s more probable that valuations revert downwards towards their longer-term averages— The political cycle we are entering may also reduce both the economic incentives of PE funds as well as result in higher interest rates, which will over time present a further drag on valuations.

Low Growth Environment

A high growth economic environment (4+% annual GDP growth) can cure a lot of sins. While a temporary surge in growth is anticipated in 2021 as the nation returns to normal after Covid, nearly all economists forecast sluggish growth over the medium to long term. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts GDP growth will average 1.6% over the next 30 years. These anemic rates are primarily due to our significant public debt burden, which is only expected to increase as the aging population and rising healthcare costs drive higher Social Security and Medicare spending.

Retroactive Tax Increases are Possible

The new Administration and Congress have signaled their plan to introduce legislation that will increase tax rates. We know they will increase, the real question is when? Impeachment proceedings and Covid relief stimulus packages will likely take priority once the new Administration is sworn-in, functionally delaying the introduction of any bills to increase taxes. There are several relevant categories that are likely to be raised: corporate tax rates, top bracket of ordinary income rates, Social Security payroll thresholds, and capital gains rates. The last category is particularly important because business sellers typically benefit from the relatively low long-term capital gains rate of 20% relative to ordinary income rates, which are significantly higher.

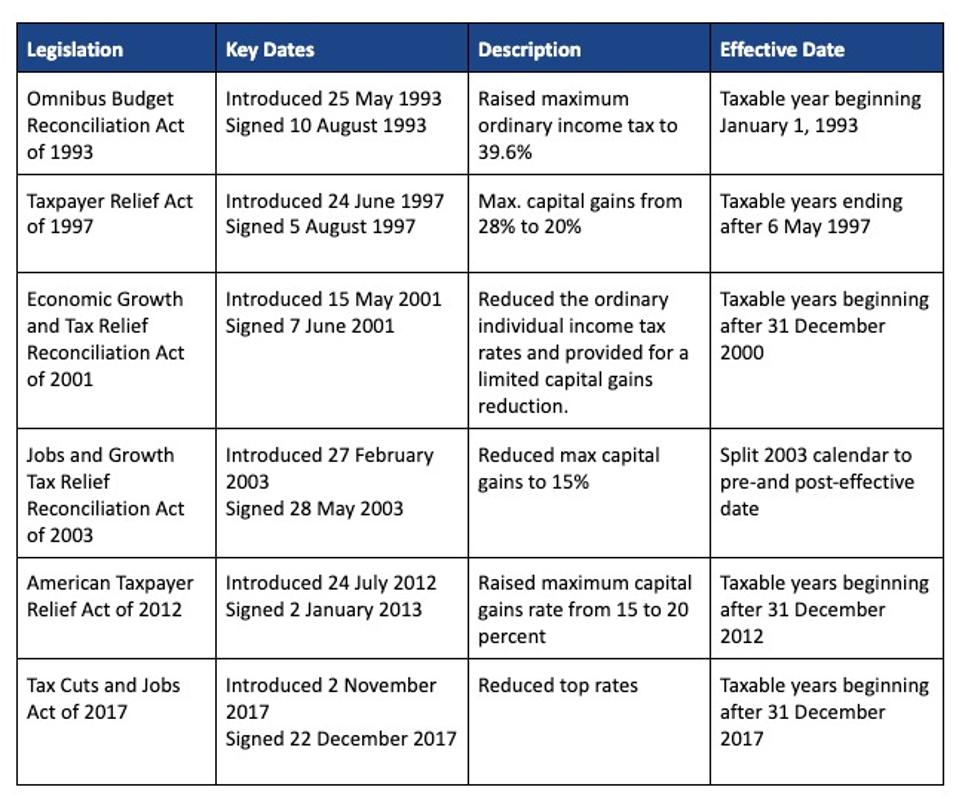

Historically, tax legislation has taken 6 to 9 months to be signed into law from the time it is introduced. The effective date of these new taxes can either be A) retroactive to the beginning of the year (the Supreme Court has affirmed the legality of tax increase retroactivity), B) begin at the time of passage, or C) start at the beginning of the following year.

Over the past 30 years, three tax changes (1993, 1997, and 2001) were effective retroactive to the start of the year in which they were signed, one (2003) split the year in two and applied different treatments (since it was passed in the middle of the year), and two of them (2012 and 2017) started at the beginning of the following year:

Politics of tax raises

It is important to note that most of the above examples were tax decreases. It is easier politically to lower taxes than to raise them and Congress is more likely to make tax reductions retroactive as this is perceived as a “gift” to voters. While legal, retroactive tax increases feel inherently unfair (as affected individuals do not have advanced notice of the specific policy details and cannot prepare accordingly) and therefore requires greater political muscle to invoke them. The razor-thin margin that Democrats have in the Senate and the fragile economic recovery will likely have them choose the more conservative route of having capital gains take effect shortly after the passage of legislation or at the beginning of the following calendar year (likely January 1, 2022).

Takeaway

Although tax rates are unlikely to rise in the first half of the year, the time to start a thorough M&A sale process is now. While a well organized middle-market business can be sold in as little as 3 to 4 months, the average takes approximately 8 months. Time is of the essence and the risk only increases the further along we get.