This article was originally published in Forbes.

Private equity’s (PE) playbook for creating investment value is relatively basic and straightforward (though not necessarily easy). Building on my prior article, The Alchemy of Private Equity Explained, this article delves into the strategies and tactics used by PE investors to boost EBITDA (Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization, commonly used as a proxy for cash-flow) and valuation multiples. Studying the approach of investors who are singularly focused on maximizing exit values can provide valuable insights for owners and managers who seek to achieve peak performance, especially if they might be considering a sale of their business in the near-to-mid term.

Financial Engineering

Referred to as “leveraged buyouts” during the 1980s, private equity acquisitions involve purchases of companies using a considerable amount of debt—leverage—that both amplifies the potential upside returns and the prospective downside risks. PE investors, typically funds, use the underlying value of the acquired business as collateral for these loans.

Generally speaking, PE aims to minimize the amount of capital they put into a deal, preferring instead to borrow from banks, other lenders, and even the seller to fund the bulk of the purchase. This is because the cost of capital associated with debt financing—functionally, the expected interest rate— is lower than that of equity (particularly since interest is tax deductible). Minimizing the cash outlay also provides investors with the optionality to more easily walk away from the business if the performance deteriorates, minimizing losses.

Unlike traditionally conservative banks, which tend to require restrictive loan covenants—and often, personal guarantees—nonbank private lenders have been willing to provide significantly higher amounts of debt relative to the value of the acquisition target. At present, total Debt-to-EBITDA multiples are averaging roughly 4-4.5x for deals under $250 million in enterprise value (EV) and 7x for larger buyout transactions.

Given their relatively high post-transaction debt levels, PE-owned companies generally face significant restrictions with respect to making dividend distributions. Consequently, virtually all cash flow that is not reinvested in the business is allocated toward paying down debt. Over time, this decreases the company’s leverage, which helps build up equity. However, should the business be delevered to comfortable levels without any sale being imminent, most PE investors will then opt for a “debt recapitalization,” which involves taking on fresh debt and distributing the cash raised as a one-time dividend.

There are various financing source that PE firms rely on beyond providing the equity capital they directly invest to fund acquisitions. These include:

● Senior loans

○ Traditional terms loan that use the company’s assets as collateral and typically contain strict financial covenants (e.g., total debt/ EBITDA, fixed charge coverage, etc.).

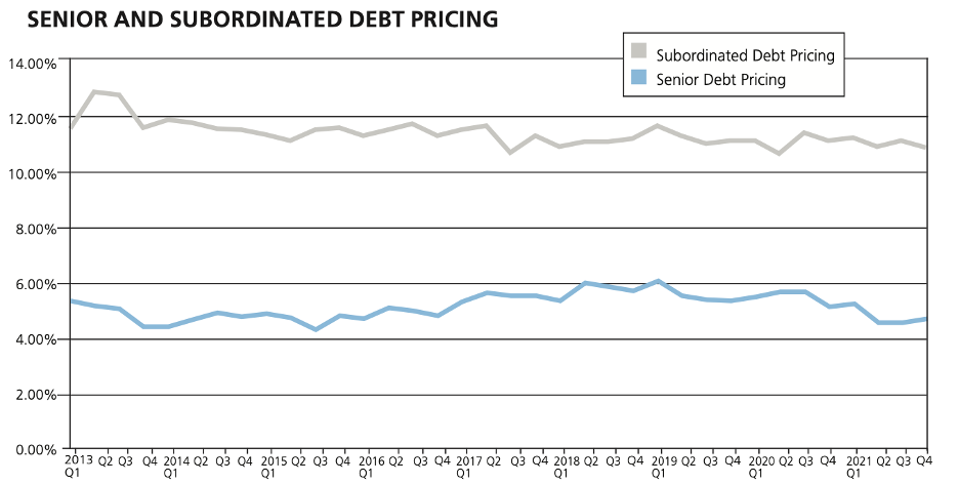

○ Financing costs are currently averaging 4.5–5.5%, priced on a floating rate above LIBOR

● Subordinated loans (often referred to as mezzanine or second-lien loans)

○ Term loans that are subordinate to senior debt and are generally based on the borrower’s ability to generate cash flow rather than the value of collateral. These loans often have flexibility regarding amortization (paydown of principal) and may also allow some or all of the interest to be accrued (referred to as Payment-in-Kind or PIK). This is particularly beneficial to borrowers who need to carefully manage their cash flows early in the investment lifecycle. Frequently these lenders will receive as consideration a small percentage of equity warrants to enable the lender to participate in some of the deal’s upside.

○ Financing costs are currently averaging 10.5–12.0%.

○ Increasingly popular are unitraunche loans that essentially combine both Senior and Subordinated loans into a single loan with a blended interest rate, saving some cost and complexity.

○ Seller financing: Terms can vary widely, and reflect whatever can be negotiated with the seller, but these obligations are generally subordinated to other debt.

Debt pricing has slightly declined over the past decade.

GF DATA LEVERAGE REPORT (FEB. 2022)

● Preferred equity

○ Senior to the common equity holders, this flexible capital generally pays fixed dividend payments that generally can be deferred and accrued. Unlike debt, these payments are not tax deductible.

○ Expected rates currently average 15 to 20%. While it results in less dilution relative to common equity, most of the time there is some ability to convert allowing it to benefit from some upside. Preferred equity is often used as a tool to shift risk, functionally enabling investors to place a “floor” on their downside at the expense of reduced upside.

● Other available capital sources

○ Sale-and-leaseback transactions involving equipment and/or real estate: Owned assets are sold and then leased back to the company by way of a long-term agreement.

○ Lines of credit: Typically provided by banks, these revolving credit facilities are generally small and are primarily used to finance working capital or seasonal fluctuations.

○ Seller rollover equity: Typical PE deals require the seller to reinvest a portion of their proceeds into common equity at the same terms and conditions as the PE investor, which represent 15 to 30% of the total common equity, on average. This not only reduces the amount of equity capital invested by the PE investor, but is viewed as critical to aligning interests and ensuring a smooth orderly ownership transition. Sellers often appreciate this opportunity to invest as the financial returns are typically much greater than public market investment alternatives.

Historically, PE has been able to deliver attractive returns simply through deploying an aggressive capital structure with little operational changes. The near-zero interest rates since the Great Recession has spurred sizable increases in valuation multiples putting pressures on investment returns. Consequently, PE investors are focusing even more aggressively than in the past on reinvesting in and improving the operational performance of the portfolio companies they own to continue generating above market returns.

Boosting EBITDA

According to the 2021 Pepperdine Private Capital report, PE investors underwrite their investments with an average EBITDA growth expectation of 20% annually, significantly above industry norms. To bolster the odds that they can deliver this kind of superb financial performance PE typically focuses on three key elements:

● Organic growth

○ Selling more products and services to current customers through improved sales and marketing efforts

○ Expanding the range of products and/or geographical markets

○ Typically PE investors front-load any organic growth efforts that have a longer payback period. After 2-3 years, most initiatives will be focused exclusively on those that allow for a quick payback (to avoid being penalized for growth, as EBITDA tends to be lower until new growth investments start reaching their potential)

● Growth through acquisitions

○ Seeking out operational synergies (e.g., eliminating duplicative overhead, facilitating the cross-selling of complementary products)

○ Favoring acquisitions over de novo expansions, which often take longer to reach their full potential. This allows for greater optionality as far as exit timing goes because there is less pressure to wait for growth initiatives to start paying off.

● Improved margins

○ Cutting costs through improved purchasing, more efficient operations, etc.

○ Increasing the use of technology and automation, particularly in the current environment being impacted by wage inflation and difficulties finding talent

PE firms often accelerate these efforts by providing their investments with access to industry and functional expertise. While outside consultants are used, it is becoming increasingly commonplace for PE investors to have their own internal teams—often referred to as “operating partners”—to provide dedicated assistance to portfolio companies to help them maximize performance. Those who are farthest along in this regard will often make available a “tool chest” of resources, including:

● Internal training and conferences, where portfolio company CEOs can share best practices and support one another

● Fractional shared expertise that is often too costly for an individual company to secure on their own (e.g., Chief Digital Marketing Officer, Chief Cybersecurity Officer, General Counsel, executive recruiters, etc.)

● Access to technical resources such as digital marketing expertise

● Group purchasing discounts for commonly used products and services (e.g., insurance, accounting services, office supplies, etc.)

Source: CEPRES Market Intelligence

BAIN 2022 PRIVATE EQUITY REPORT

Mathematically, there are three levers that can be pulled to increase a company’s valuation: a) increasing revenues, b) increasing margins of those revenues, and c) increasing the EBITDA multiple applied against it. The largest (and increasing) portion of value creation has come from the latter, which will be address next.

Expanding Multiples

Most PE investments have benefitted from the trend of rising valuation multiples over the past decade. Additionally, while there are a number of different underlying factors, valuation multiples are strongly correlated with company size, according to Pursant’s DEAL Insider Q4 2021 report. Mark Herbick, CEO of Pursant explains “aside from being associated with more sophisticated businesses, this phenomenon occurs because lenders are willing to provide more financing and buyers tend to be larger with a lower cost of capital.”

Source: Pepperdine Private Capital Markets report, GF Data

PURSANT DEAL INSIDER Q4 2021 REPORT

This has spurred a growing number of PE investors to pursue a “buy-and-build“ strategy, which typically involves a “platform” company aggregating and integrating smaller add-on acquisitions to achieve rapid growth and scale. Upon exit, the investment benefits from the arbitrage between the higher EBITDA multiples that larger enterprises command and the lower multiples paid across for the various smaller acquisitions. In fact, a Boston Consulting Group study found that in the lower middle-market, returns from this strategy are nearly 2.5x greater than standalone investments without M&A. The relative benefit of this strategy appears to decline as deal sizes increase.

Professionalizing the business

One caveat, of course, is that there is more to this investing alchemy than the simple buy-and-build moniker might suggest. As Warren Buffett once quipped, “you can’t produce a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant.” Similarly, slapping multiple mediocre businesses together is more likely to create a mess than a success story. Indeed, one reason why PE-owned business generally sell at a premium relative to founder-owned counterparts is because they are typically more robust, having implemented operational, financial, and organizational best practices during their tenures as portfolio companies.

For these firms—and even managers and owners who might be considering a do-it-yourself PE-style value-creation approach—one common objective is to create and flesh out an organizational structure that can readily accommodate both an uptick in internal growth and potentially multiple acquisitions over time. Such efforts could include:

● Standardizing and automating, where available, critical processes

● Enhancing financial reporting and dashboards

● Upgrading IT systems (e.g., ERP, accounting)

● Building a strong leadership team, supported by promising middle-managers

● Facilitating a healthy culture, with below industry-average turnover

● Compiling and organizing critical documentation necessary for an exit from the get-go, allowing for a quick sale should the opportunity arise

But there is even more to it. In situations where leverage is high or there is a desire for a rapid exit, management is always under persistent pressure to perform. Under these circumstances, nearly all successful PE-owned companies understand that they have little choice but to develop cultures biased toward action, reinforced by a strong sense of urgency, and centered around a mutual commitment to accountability and performance.

Executing a value-creation plan

Another common element in PE transactions is the development of a comprehensive strategic plan. As the process of due diligence wraps up before a deal closes, nearly all PE investors will leverage the insights the have gleaned during the process to develop a multiyear value-creation strategy that kicks off with a 100-day plan. The plan develops a detailed annual budget corresponding to the initially underwritten (3 to 5 year) investment case. The broader strategic roadmap generally begins with envisioning the M&A positioning strategy that maximizes the company’s value at exit, and systematically addressing deficiencies and pursuing targeted growth opportunities with a focus on what a prospective acquirer will likely value most. This includes:

● Tilting future growth towards product, channel, and customer mixes with the most attractive profiles

● Identifying and, where necessary, reframing the business toward industry-specific trends that are expected to be in vogue (such as “technology enabled” businesses) and command higher valuations

● Focusing growth upon a specific industry or geographic niche to become a market leader within it (assets perceived as unique or “scarce” often command outsized multiples)

● Characterizing the most likely buyers—including specific companies—and addressing their strategic priorities

● Attempting to address common value detractors, when possible:

○ Excessive customer concentration

○ Orientation toward project-based fees or short-term contracts that easily can be terminated

○ Lack of non-compete agreements for critical positions or contracts validating ownership/ terms of important intellectual property

○ Problematic litigation

○ Unhealthy dependency on a single individual (also known as key-man risk) without a succession plan

Disciplined implementation occurs through weekly or biweekly meetings where progress is measured against a detailed action plan that delineates specific tactics, their deadlines (and interim milestones), responsible parties, and critical dependencies. One to two years ahead of an anticipated sale, the M&A positioning strategy is generally revisited and prioritized.

Engaging in active board ownership

Generally speaking, PE investors believe in finding and hiring the right CEO (and often CFO) for the job and holding that individual accountable for achieving mutually agreed-upon growth objectives (failure to do so generally results in replacement). But that does not mean they take a hands-off approach when it comes to the strategic objectives and day-to-day operations of the portfolio companies they invest in.

According to a May 2021 commentary by McKinsey, Climbing the Private-Equity Learning Curve, “New CEOs of PE-held companies may find that they need less time for formal board meetings overall because board members will already be highly engaged between meetings—visiting sites, customers, and suppliers and conducting ad hoc calls to advise management on opportunities or threats arising between board meetings.” Attention and involvement increases if the investment is performing poorly.

Board meetings also tend to follow refined formats that ensure efficiency and effectiveness. These quarterly (or possibly monthly) meetings are highly data-oriented and focus on analyzing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and financial performance relative to the agreed upon budget and initial investment plan. As circumstances change, the strategic plan may be revisited and modified, along with its corresponding budget.

Ensuring interests are aligned

To ensure that everyone is on the same page in terms of creating value and following through on the agreed plan of action, most PE investors create a management incentive pool amounting to 5-8% of the company’s total equity (this ownership claim is nearly always subject to the fund receiving back its investment and occasionally achieving a baseline performance level). Additionally, a broader set of executives typically receive Short and Long Term Incentive Plans (STIP and LTIP, respectively) that often are tied to the budget or (three to five year) investment case. If the business performs well, the managers responsible stand to reap significant upside. These incentive packages often are associated with non-compete agreements and vesting structures that encourage post-transaction retention—both factors important to subsequent buyers.

Putting “window dressing” in place

In reality, not all of the tactics that some PE investors employ improve the long-run performance or sustainability of the business. Some are more oriented toward improving the optics of the business prior to sale. While most prospective buyers will identify and adjust for these factors, there’s a decent chance that one or more will give the benefit of the doubt when underwriting the transaction, particularly in a competitive sales environment. Confidential conversations with a handful of PE-backed CEO’s mentioned the following:

- Buying equipment and other assets rather than leasing them, as depreciation will get added back in calculating EBITDA

- Making capital expenditure investments that reduce operating expenses (even if suboptimal), since EBITDA is unaffected

- Utilizing consultants for tasks that should be performed internally, in the hope that the expenses will be accepted as nonrecurring add-backs

- Throttling back marketing and other investments in future growth immediately before selling to maximize short term contribution.

- Adjusting accounting assumptions to improve earnings (e.g., reducing bad-debt, warranty, or inventory reserve assumptions, changing resale value estimates, etc.)

- Modifying synergy estimates on recent acquisitions to reflect higher pro forma EBITDA

Exiting through a competitive sales process

PE investors generally prefer to buy in off-market, privately negotiated transactions instead of participating in competitive auctions, as they tend to result in lower entry valuations and better deal terms. The opposite holds true when they want to exit. In the vast majority of cases, they will retain an investment bank to run a competitive sales process designed to drum up interest amongst the best-suited strategic and financial buyers with the goal of maximizing the sales price. These advisors are skilled negotiators who zealously advocate for their client’s interests.